File Under: Voices from the Underground

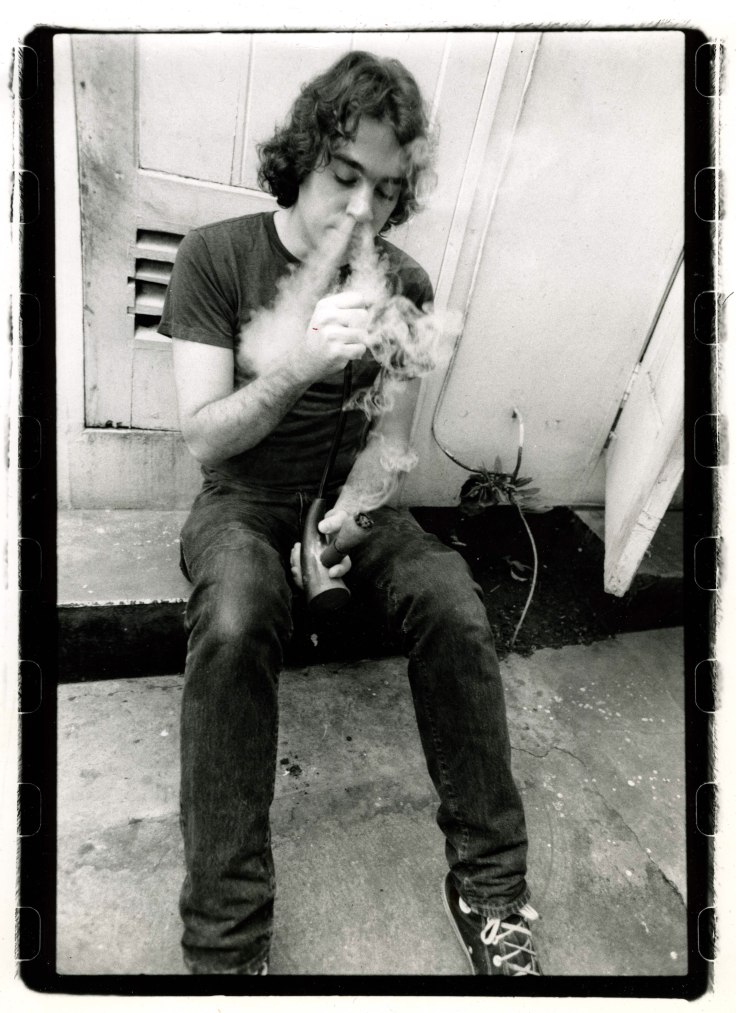

Chris Simunek didn’t just write about cannabis culture; he lived it. He wasn’t on the sidelines; he was deep in it, chronicling a world that thrived before legalization softened its edges. Back when High Times was more than a brand and weed was a felony, not a flavor.

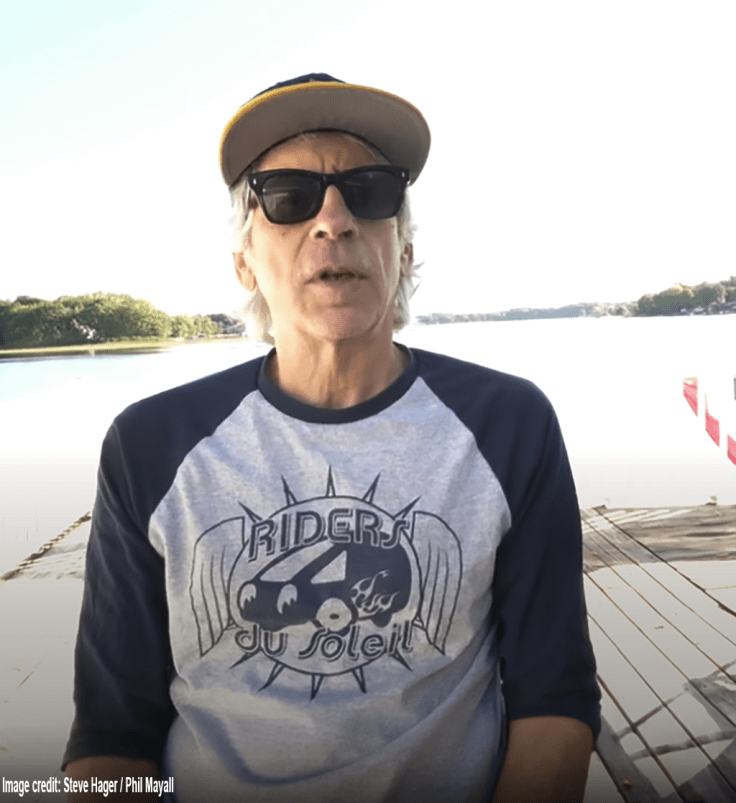

Chris joined High Times in 1993 after a chance encounter with editor-in-chief Steven Hager at the Continental, a New York nightclub. Chris had lent his friend a copy of Journey to the End of the Night by French novelist Céline. Hager saw the book and struck up a conversation. Chris invited him to a fiction reading, where he read from his unpublished novel, No Easter, about a seven-hundred-foot monster that destroyed everything he hated. On the strength of that, Hager invited him to the office. A few days later, Chris walked in, no résumé, no formal pitch. His first assignment was covering Pot Smokers Anonymous.

“It was still underground. High Times was a meeting place for people who didn’t quite fit in. The marijuana movement wasn’t made up of normal people. Everybody was some shade of fuckup. That’s why I felt comfortable.”

For Chris, cannabis culture wasn’t about tie-dye or cliché stoner aesthetics. It was about the unspoken connection between outlaws, artists, and rebels.

“Marijuana was like a secret handshake. I could talk to bikers, hippies, criminals, and rock stars. We didn’t dress the same, but we spoke the same language.”

Back then, it wasn’t safe. The growers, smugglers, and activists who kept the scene alive were constantly being hunted. And the journalists covering them weren’t far removed from the heat.

“When people spoke up about weed back then, it meant something. It wasn’t content, it was a risk.”

Chris gravitated toward people who weren’t average. He chased stories that existed outside the mainstream, encounters that weren’t polished but real.

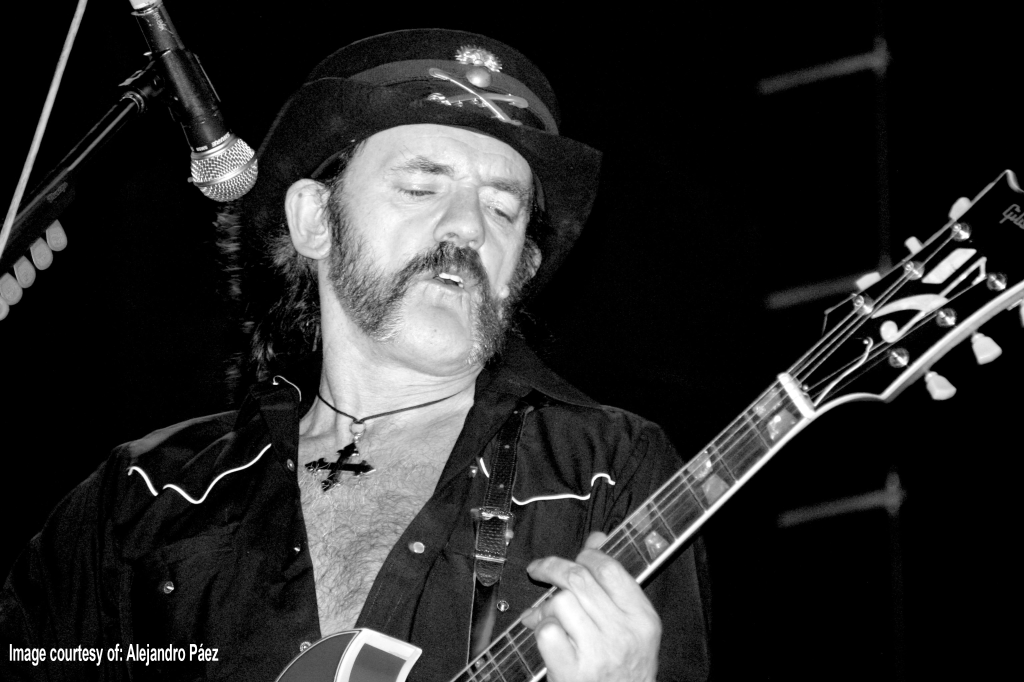

One of them was Lemmy, Motörhead’s frontman, a rock and roll warlord if there ever was one. Chris spotted him alone at a hotel bar and introduced himself.

“Hey Lemmy, it’s Chris from High Times, just wanted to say hi.”

Lemmy barely looked at him.

“All you fuckers write about is ecstasy and marijuana. You never tell the truth about speed.”

Chris didn’t hesitate. “Let’s tell the truth about speed,” he said.

Lemmy took him upstairs, poured a heavy glass of Jim Beam, turned off the recorder, and dumped a pile of powder on the table. No lines. No cut. Just raw powder, fingers, and dabs.

“I wasn’t completely unfamiliar,” Chris admitted. “But I wasn’t too familiar either. Lemmy nodded at me. So I did what he did.”

Then Lemmy told him, “Finish it up. It ain’t gonna kill ya.”

Chris did.

“I was up ‘til the next afternoon. Plenty. More than enough.”

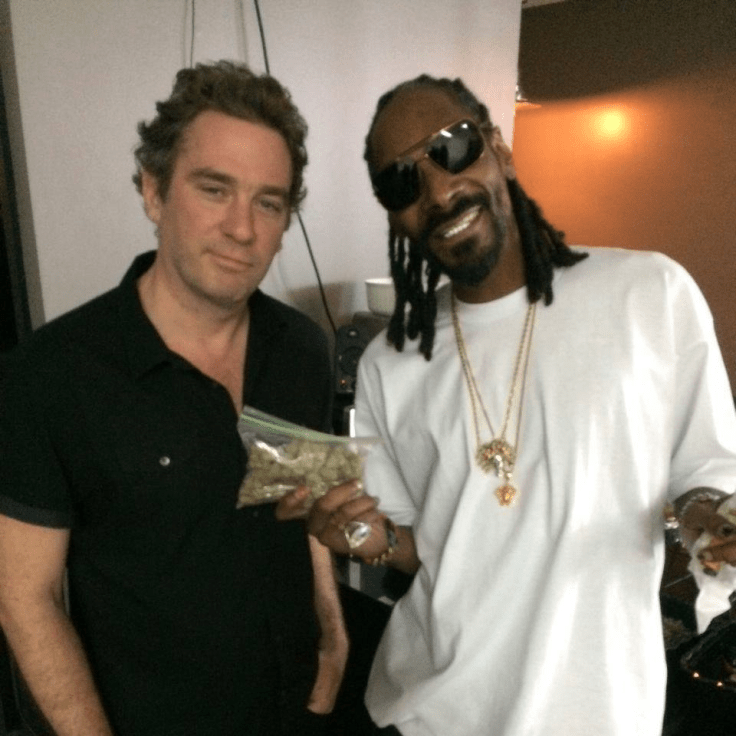

Not every run-in was that intense. His High Times interview with Snoop Dogg and Wiz Khalifa went nowhere.

“I asked what kind of pot they liked, then froze,” Chris recalled. “Snoop looked at me and said, > ‘You must have more questions in that little notebook of yours.’”

Chris shrugged.

“I didn’t grow up listening to those guys. And Snoop’s been interviewed more than almost anyone alive. What are you supposed to ask?”

Then there was Joe Strummer.

Chris found himself standing next to The Clash’s frontman at a birthday party for a photographer friend. A joint was being passed around, and conversation turned to Jamaica.

“He told me how he and Mick Jones almost got killed going into the hardcore areas of Kingston. I believed it. I almost got killed there, too.”

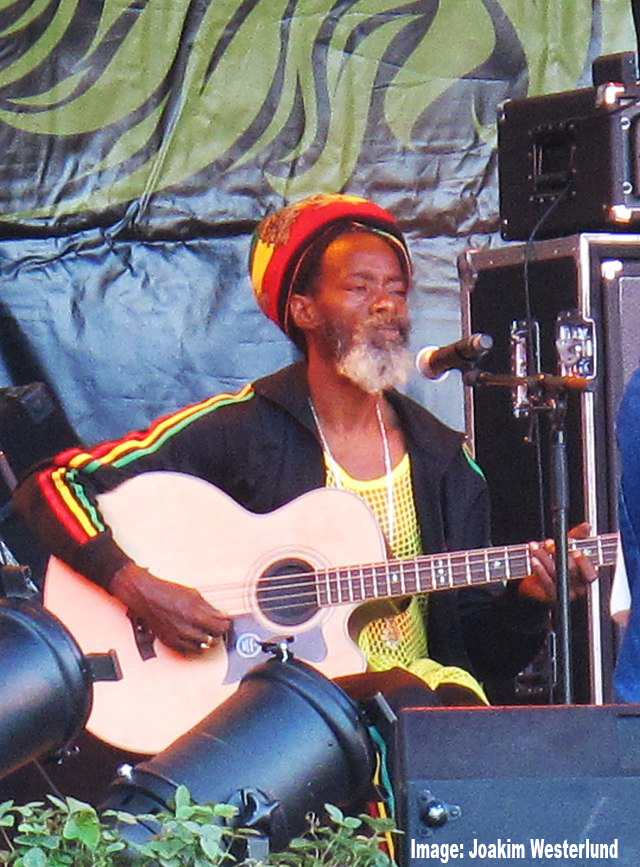

Chris traveled to Jamaica often for High Times, usually alongside photographer Brian Jahn. They stayed with legendary reggae guitarist Chinna Smith, who played with Lee Perry and the Upsetters.

Chinna’s house wasn’t a studio or a hotel. It was a Rasta stronghold, a place where music spilled out of windows, the chalice never stopped passing, and conversations ran deeper than anything happening in an editorial meeting.

One night, they were invited to a Nyabinghi, a sacred Rastafarian ceremony.

“My friends wandered off. All peace and love. But then people started circling. It wasn’t fun.”

Someone shouted, “Slay the white dragon.”

Chris realized he was the only outsider still standing near the bonfire.

“There was a crowd of people screaming they wanted to throw us into this gigantic fire. This wasn’t a campfire. It had a tree trunk in it, and it was roaring. You could feel it pulling oxygen from the air.”

The elders stepped in and shut it down before it could escalate. Chris got out fine, but years later, the retelling sparked backlash.

“It wasn’t the article that pissed people off. It was someone saying, ‘Hey, did you read that crazy story about Chris almost getting killed at a Rasta ceremony?’ I don’t think they even read the story. But it turned into a thing.”

For Chris, it was a lesson in how fast myth replaces nuance once a story takes on a life of its own.

FOR THE CULTURE BY THE CULTURE

The Drug Test Lie Finally Cracks in New Mexico

New Mexico’s Senate Bill 129 challenges the long standing assumption that a positive cannabis test equals impairment. By separating outdated drug testing from actual workplace…

How Cannabis Can Cost You Your Gun

Federal law still allows cannabis use to strip Americans of firearm rights without proof of danger or misuse. As the Supreme Court weighs United States…

Now, High Times is mostly memory.

“I’ve been gone almost ten years. I never met the last round of owners. But it was sad to see it go under. That magazine meant something to people. It meant something to me. There were ups and downs, but in the end, I feel like I was part of something unique. That’s the reason I wrote As the World Burns, because I wanted to describe life before the Green Rush, this culture that endured a lot of hardship but also had a lot of fun.”

There’s talk of a reboot, but it’s just the name. The era is gone.

While the brand name flickers back to life under new hands, Chris isn’t looking backward. He’s writing forward, toward the stories that never made it to print, the ones still burning under the surface.

He’s working on a new book. Not a remix of Paradise Burning, but new stories, from a different voice. Less posture, more clarity.

“I wanted to describe what life was like before all this. This culture went through a lot, but we had fun. We might’ve looked strange, but we were right about the drug war. And now, yeah, you can walk into a store and buy marijuana like a civilized person.”

Then he paused.

“When I started, we were being hunted like animals. As far as law enforcement was concerned, we weren’t business owners. We weren’t activists. We were targets. And most of the people I knew didn’t get the second chance that legalization gave the industry.”

I asked him: What’s one thing about working for High Times you had to find out for yourself?

“I had to learn how to be a journalist. I’d only ever written fiction before. A lot of great writers passed through High Times over the years, and there were a couple still there when I started. I didn’t want to look like some bullshit artist to them, so I had to learn the craft.”

There’s more where this came from. In Part Two, Chris aims at the modern cannabis industry, the collapse of outlaw culture, and the unfinished business that drove him to finally write the sequel to Paradise Burning.

©2025 Pot Culture Magazine. All rights reserved. This content is the exclusive property of Pot Culture Magazine and may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations in critical reviews.

Discover more from POT CULTURE MAGAZINE

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a comment